College History

SCROLL TO EXPLORE

The first mention of the name Brasenose, which likely derives its name from a brazen (brass or bronze) door knocker in the shape of a nose.

Before the foundation of Brasenose College in 1509, a central part of the area now called ‘Old Quad’ was occupied by an institution known as ‘Brasenose Hall’. Various other halls and houses occupied the site alongside Brasenose Hall, but very little is known about the Hall itself. In the Survey of Inquisition of 1279, it is stated that Oxford University held ‘a house called Brasennose… in the parish of St Mary the Virgin’. Our ‘Medieval Kitchen’ is thought to have been the kitchen for Brasenose Hall, and dates from around the 15th century (the oldest building onsite).

Figure 1 Brazen nose in the stained glass in Hall.

Brasenose Hall students take knocker to Stamford, Lincolnshire

In 1333, a group of Oxford students migrated to Stamford in Lincolnshire, including among their number ‘Philippus le maniciple ate Bresnose.’ It is thought that a Brasenose Hall student took a door knocker with them, which was left behind when they were ordered to return by the King. In 1890, Brasenose College purchased a house in Stamford which had an ancient door knocker, thought to be the original knocker from Brasenose Hall, thus reuniting it with its namesake. The knocker now hangs in its rightful place above High Table in the dining hall.

Figure 2 Brazen nose knocker above High Table.

Brasenose College founded

It is difficult to establish exactly when Brasenose Hall became Brasenose College. Two of the former Principals of the Hall (Matthew Smyth and John Formby) became Principal and Fellow, respectively, of the newly formed College.

The founders were Sir Richard Sutton, a lawyer, and William Smyth, Bishop of Lincoln. Both were from the north-west and the College has retained strong links with Cheshire and Lancashire throughout its history. Smyth provided for the expenses of the building and Sutton acquired the property for the site.

Figure 3 The Founders in the stained glass in Hall

Foundation Charter granted by Henry VIII

The Royal Charter established a College to be called ‘The King’s Hall and College of Brasenose’ for the study of sophistry, logic, philosophy and, above all, theology. In the beginning, the Founders’ statutes stipulate a Principal and 12 scholar-fellows, alongside servants including the Steward, Manciple, Bible-clerk, Butler, Head Cook, Porter, and the Laundress, who was not allowed inside the College gates.

Figure 4 Foundation Charter

Brasenose acquires St Mary’s College (Frewin Hall)

The site was granted to Brasenose in 1580, and was let out to tenants (including Dr Richard Frewin, from whom it gets its name) until it became student accommodation in 1946. The Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII), resided at Frewin in 1859-1860 when he was a student at Oxford University.

Figure 5 The Prince of Wales at Frewin (PIC 2 A1)

Visit of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I visited Brasenose in 1592 as part of her visit to Oxford. In 1572 Alexander Nowell had petitioned Queen Elizabeth I to re-found the Grammar School of Middleton in Lancashire, where he had been a pupil. It was to be governed by the Principal and Fellows of Brasenose College. He later also persuaded the Queen to endow the College.

Figure 6 Seal affixed to Elizabeth I Charter (Middleton I)

Visit of James I

John Middleton, Childe of Hale visits Brasenose

One of the legends of Brasenose College involves John Middleton, a man from Hale in Lancashire reputed to have reached 9’ 3” in height. He is said to have visited College on the way back from a contest with King James I’s wrestler in 1617.

There is a story that Middleton (known as the Childe of Hale) left an impression of his hand in College, which is supported by Samuel Pepys’ diary for 9th June 1668.

The College Boat Club has a tradition of naming the First VIII after the Childe, and the crew wear the colours of the outfit he wore on his trip to London (yellow, purple and red).

Civil War

College surrendered most of its plate to support the King during the Civil War. Principal Samuel Radcliffe rebelled against the Parliamentary Authorities, refusing to give up his position or hand over his keys to the Treasury or archives. He died under armed guard in the Principal’s Lodgings.

Building of Chapel, Library and Cloisters

On 18 June 1656 the foundation stone of the new Chapel was laid. The new Library was completed in 1663, and the Chapel was consecrated on 17 November 1666. Nine of the original Chapel cushions are in the Archives, alongside a bill which details the purchase of the cushions.

Figure 7 17th century Chapel cushion with the arms of Founder Richard Sutton

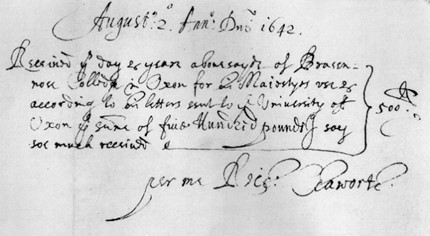

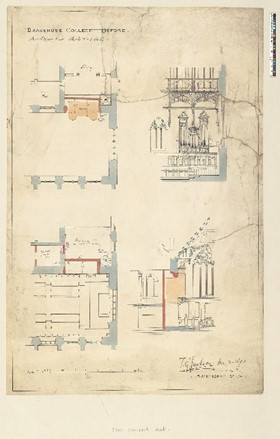

College Brewhouse Built

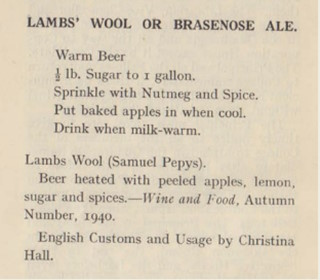

Between 1695 and 1697 a brewhouse was built on the college site, and Brasenose Ale (or Lambs’ Wool) became a popular beverage within the College, so much so that there is an annual tradition of writing poetry in praise of the Ale, known as Ale Verses. These are still recited each year on Shrove Tuesday. In 1826 a new brewhouse was built behind the kitchens, but brewing ceased in 1889 when the building of New Quad necessitated the removal of the brewhouse. This resulted in a brief end to the verses, but they were resurrected in 1909.

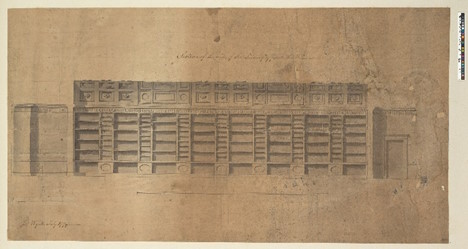

James Wyatt redesigned the Library interior

The interior of the library was rearranged and the ceiling decorated by James Wyatt in 1779-1780.

Figure 8 Section of the Side of the Library Opposite the Windows by Wyatt, Jul 1779

Open Cloisters converted to rooms (probably by Sir John Soane)

Principal Radcliffe left money in his will of 1648 to build the Chapel and ‘a buildinge upon Pillars … which will make a walke under it, ye great want of Brasennose Colledge.’

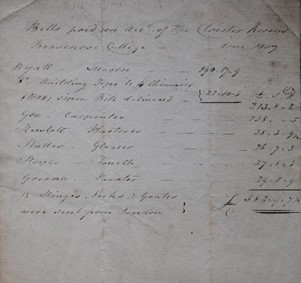

Until 1807, the cloisters were used as a place for exercise and also functioned as the College’s burial ground until they were converted into student rooms. They later became the Hulme Common Room, and later still were converted into the ground floor of the College Library.

Figure 9 Bills paid on account of the Cloister rooms Brasenose College done 1807 (Buildings 27)

Visit of Louis XVIII

A stained glass window with the arms, royal orders and crowns of England and France was put up in Hall in 1821 to commemorate the visit.

Brasenose Boat Club becomes Head of the River

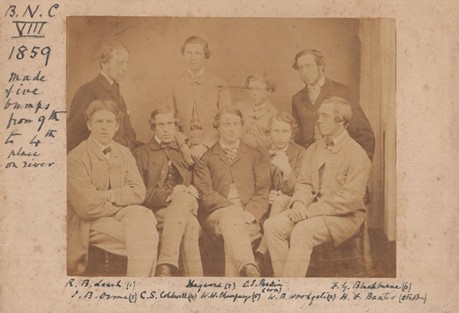

Brasenose College Boat Club is one of the oldest boat clubs in the world, and in 1815 beat Jesus College in the first ever recorded race between boat clubs. In 1839 they were Head of the Eights and in 1852, Head of Torpids.

Figure 10 Brasenose VIII 1859 (MPP 42 A1)

New Quad built

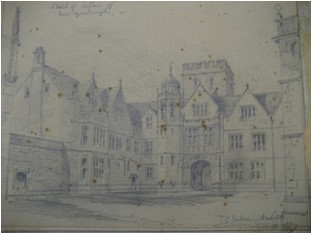

Brasenose’s new buildings were designed by Sir Thomas Graham Jackson. The project was completed in stages and completed as part of the Quatercentenary celebrations, with the foundation stone being laid in June 1909.

Figure 11 Sketch of interior of New Quadrangle by Sir Thomas Graham Jackson (B13.2)

Deer Park gets its name

In The Brazen Nose magazine of 1934, C.C. Bradford (who matriculated in 1884) recalled that he was walking through Chapel Quad with his friend R.H. Tilney (matriculated 1885) after visiting Magdalen the day before. They saw a man putting up a post and chain fence and exclaimed, ‘They are going to give us a deer-park,’ said Bradford, to which his friend, Tilney, replied, ‘By Jove, we’ll call it that’.

Figure 12 Deer Park late 19th/early 20th century (PIC 1 A4/1)

The Junior Common Room is formed.

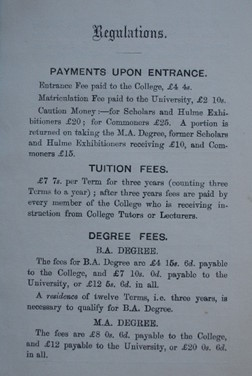

Blue Books Published

The first Blue Book was published in 1890, and was called BNC Regulations.

Figure 13 Extract from the first Brasenose Blue Book of 1890 (MEM 2 M1)

Sir Thomas Graham Jackson’s organ case

In 1890, Principal Heberden offered to give £500 for re-casing and moving the organ and Sir Thomas Graham Jackson was asked to advise on the best way to carry out the work. Jackson wrote a report suggesting various alternatives; it was decided that the old organ should be sold and a new organ should be purchased and placed over the choir screen.

Sir T. G. Jackson’s design for new organ case (not carried out, 1890) (B15.1)

Library first opened for use of Undergraduates

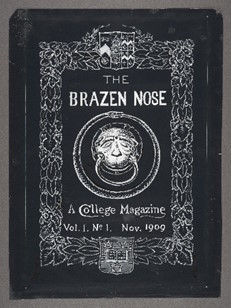

Brasenose Quatercentenary (400 years) and first issue of the College magazine, The Brazen Nose

Before the inception of The Brazen Nose, there had been an annual leaflet with information about the College and news of its members. The first surviving copy is from 1899-1900, and the last dates from 1920-1922. The leaflet for 1908/09 states, ‘If sufficient support is received to justify the enterprise, it is proposed to start a Magazine…’

Figure 15 Original drawing of the design for the first cover of The Brazen Nose by Henry George Willink (m.1870) (BN 5 A1)

Brasenose occupied by military authorities during WWI

665 Brasenose men served in World War I, 116 of whom were killed. College was occupied by several military authorities, including the Royal Flying Corps (Royal Air Force), alongside only a handful of undergraduates

*Link to blog https://brasenosecollegelibrary.wordpress.com/2014/02/25/first-world-war-centenary/

Brasenose linked with Gonville and Caius College

Brasenose formed a link with our sister college in Cambridge, Gonville and Caius. Another link already existed – Joyce Frankland was a benefactor of both Colleges.

Second World War

College was once again occupied by the military, and many Brasenose students were housed at Christ Church. 123 names are inscribed on the World War II memorial in Chapel, and there is a separate memorial to J. C. von Ruperti who was a German Rhodes Scholar.

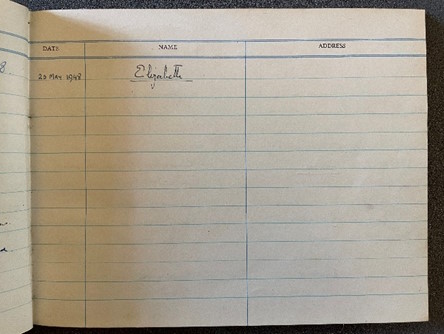

Queen Elizabeth II visit

Queen Elizabeth visited College for the first time in 1948, as Princess, and signed the visitors’ book in the Principal’s Lodgings. She visited again in on 2nd December 2009 as part of the Quincentenary celebrations.

The Powell and Moya Building is completed

The Beatles Visit Brasenose

Jeffrey Archer, then a student at Brasenose, organised for the Beatles to visit College as part of a fund-raising appeal for Oxfam. The visit was fitted in-between the Fab Four’s time spent filming the Hard Day’s Night movie

HCR inaugurated

The Hulme Common Room for graduate students was inaugurated on 23 April 1963 at a dinner, the menu of which can be seen here, using a portion of the Hulme benefaction.

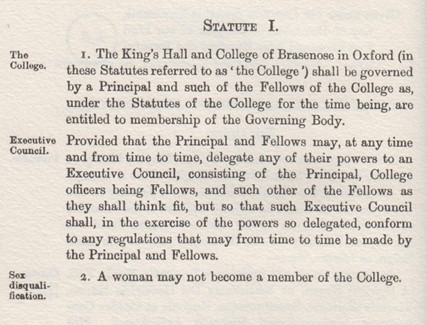

Brasenose altered the statutes to allow women to be admitted, the first Oxford college to do so

In the mid-1960s, Brasenose appointed a committee to begin looking at the proposal to admit women. In 1971, College made the momentous decision to remove the clause in its statutes which declared that ‘A woman may not become a member of the College’

The admission of women

Brasenose was one of the first 5 men’s colleges to admit women; the group also included Wadham, St Catherine’s, Jesus, and Hertford. 28 women matriculated at Brasenose in the Michaelmas term of 1974

First female College Fellow

Mary Stokes was elected to an Official Fellowship in Law in 1981, taking up the role in 1982. She was also the first woman to be awarded the Vinerian award for the best results in the law examinations

St Cross Graduate Annexe opened

Hollybush Row Graduate Annexe opened

Brasenose Quincentenary and Queen Elizabeth II visit

The Quincentenary (500th) celebrations included a visit from Queen Elizabeth II, and the Quincentenary Project began to refurbish central areas of College, including the JCR, HCR, SCR, Bar, Hall and Kitchens.

Figure 16 Principal Roger Cashmore with the Queen in Chapel

Muniment Room and Treasury renovated

The Muniment Room and Treasury are situated at the top of the Old Quad Tower, which was built between 1509 and 1522. The Treasury was (and still is) the home of the College Chest, which once contained money and important documents. It had three locks, and required the presence of three keyholders to open it. By 1710 more space was needed and the room was fitted out with shelves and drawers to store the documents. The contents further expanded downstairs into the Muniment Room, which is now fittingly the Library and Archives Office. The room was also used as a store during the English Civil War. In 2015, the space was fully renovated to restore this historic part of College to its former glory. The stonework in the Muniment Room and spiral staircase up to the Treasury was cleaned, and a bespoke display cabinet was installed in the Treasury alongside new shelving.

Figure 17 The College Chest

A new organ

In 2022 the College commissioned Orgues De Facto in Belgium to restore the original Jackson casework and design a new instrument within. The organ was installed in the College Chapel in 2024 and the inaugural concert took place in 2025.